The forecast called for rain in Yosemite on Sunday, and first Sundays are free days at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, so after dark I hit the road. Being me, I couldn't just drive to San Francisco, or maybe even to Sacramento to spend the night indoors before leaving in the morning. A more interesting drive seemed in order, so I went to just west of Patterson, CA, forty miles or so from San Jose, in preparation for driving on Mount Hamilton Road in the morning. I don't usually sleep right next to a road in a car, but I knew from experience that this road got about one car every fifteen minutes during the day, so I figured the chances of being hassled by the police or anyone else were negligible.

My morning drive on Mount Hamilton road was greatly enhanced by the free XM radio in the rental car. By this time I'd had enough of the '40s music, and was in the mood for something old. XM obliged with an excellent program of mostly pre-Baroque music, including gems like the Cantate Domino and Une Messe pour la Saint-Michel & tous les saints anges, which featured Michel Godard playing the serpent -- a cool old bass woodwind instrument descended from the cornett (whatever that is). I can't find a link to it, but here's another cool song with the serpent Tota Pulchra es Amica Mea (you are so beautiful, my love). I didn't take any pictures of the drive, but you can see a couple that don't do it justice in my Memorial Day Adventure

After San Jose and some deep-fried shrimp balls from King Eggroll (not as good as I remembered, but still worth eating), I moseyed north via the not-quite-as-windey-as-Mount-Hamilton-but-still-pretty-windey Big Basin Road and the very excellent Skyline Boulevard, with views west to the Pacific and east to the Bay. Luck was still with me, as Skyline Boulevard was surprisingly bereft of cars and I got to listen to Leonard Bernstein talking about and conducting the magnificent Symphony #3 by Brahms. Eventually I had to leave the interesting roads behind, but the drive into the city wasn't bad and I spotted someone pulling out of a parking space two blocks from the museum. The Gods of Parking smile yet again!

I decided it made sense to spend most of my museum time in their special exhibit of Tomb Treasures — New Discoveries from China’s Han Dynasty, which was in its last month. The Han Dynasty, 206 BC–220 AD, was a golden age for China, and it was one of the greatest eras in history for the development of science and technology (as was the Nothern Song Dynasty era from 960-1127 AD). Notable developments from the era include papermaking, grid-reference and raised-relief maps, steering rudders and the junks that allowed excursions on to the open sea, the wheelbarrow, derricks for drilling 2000-foot-deep bore-holes to bring brine for saltmaking to the surface. Their wells also supplied them with natural gas, which they piped through bamboo pipes to furnaces for their improved steel and salt production. They certainly buried a lot of cool stuff in their tombs:

I spent most of my Museum time deep in the tombs of dead Han guys, but it did manage to take a spin through the rest of the museum. One of my favorite rooms was the room devoted to artifacts of Tibetan Buddhism. Radically different from seeing dead guys and the stuff they wore in their tombs, this room had dead guys who were being worn, with no tomb at all. Apparently human bone serves as a reminder of our ephemerality

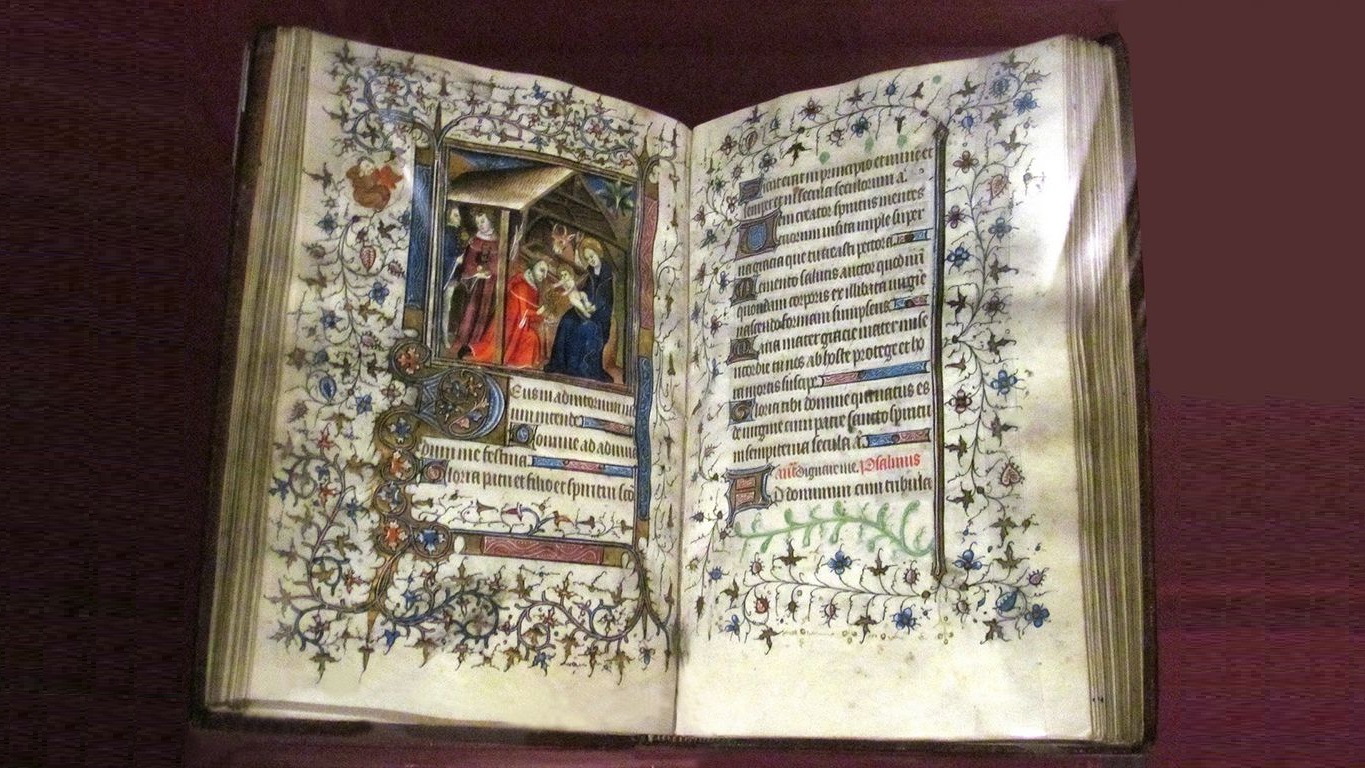

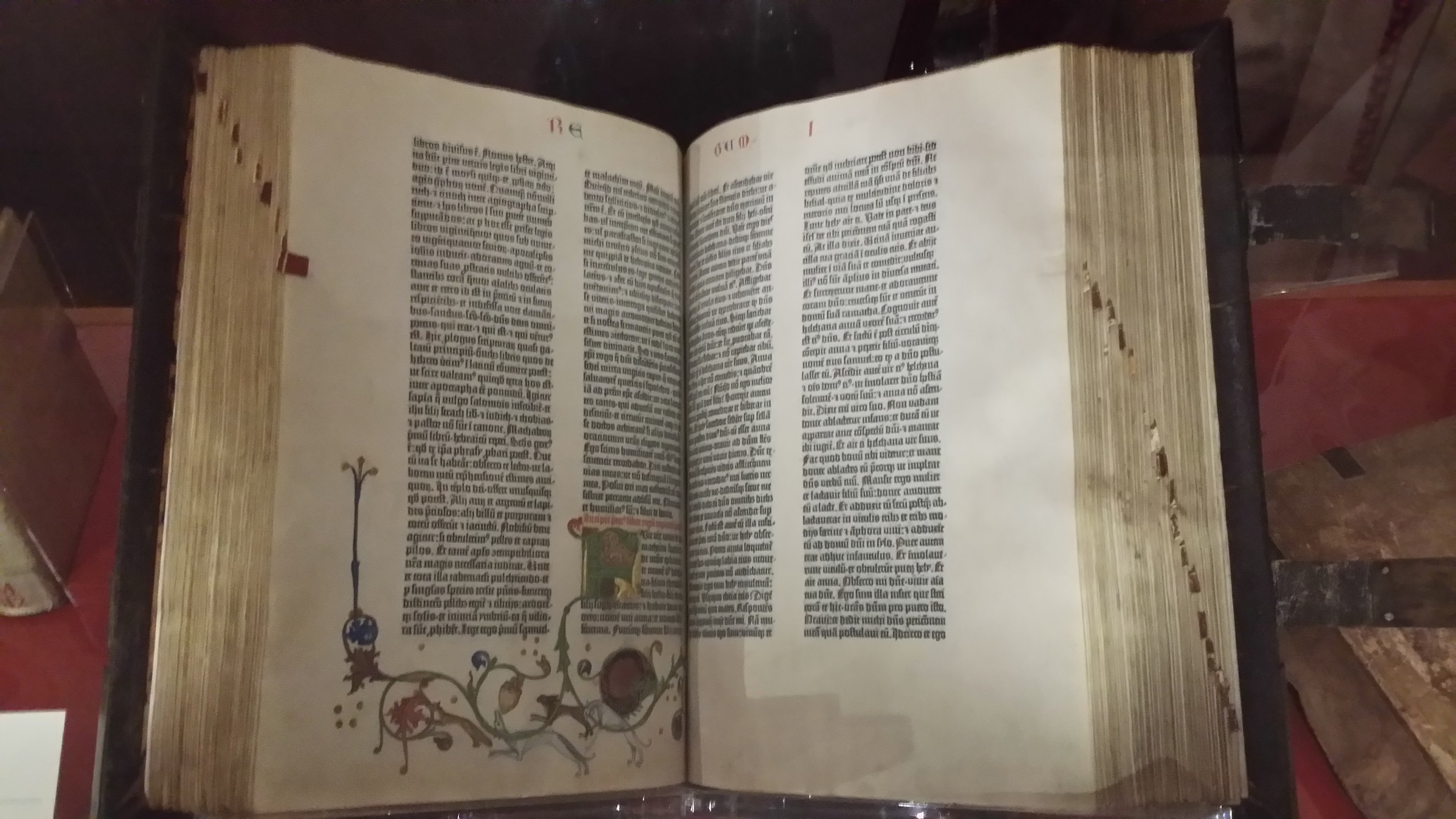

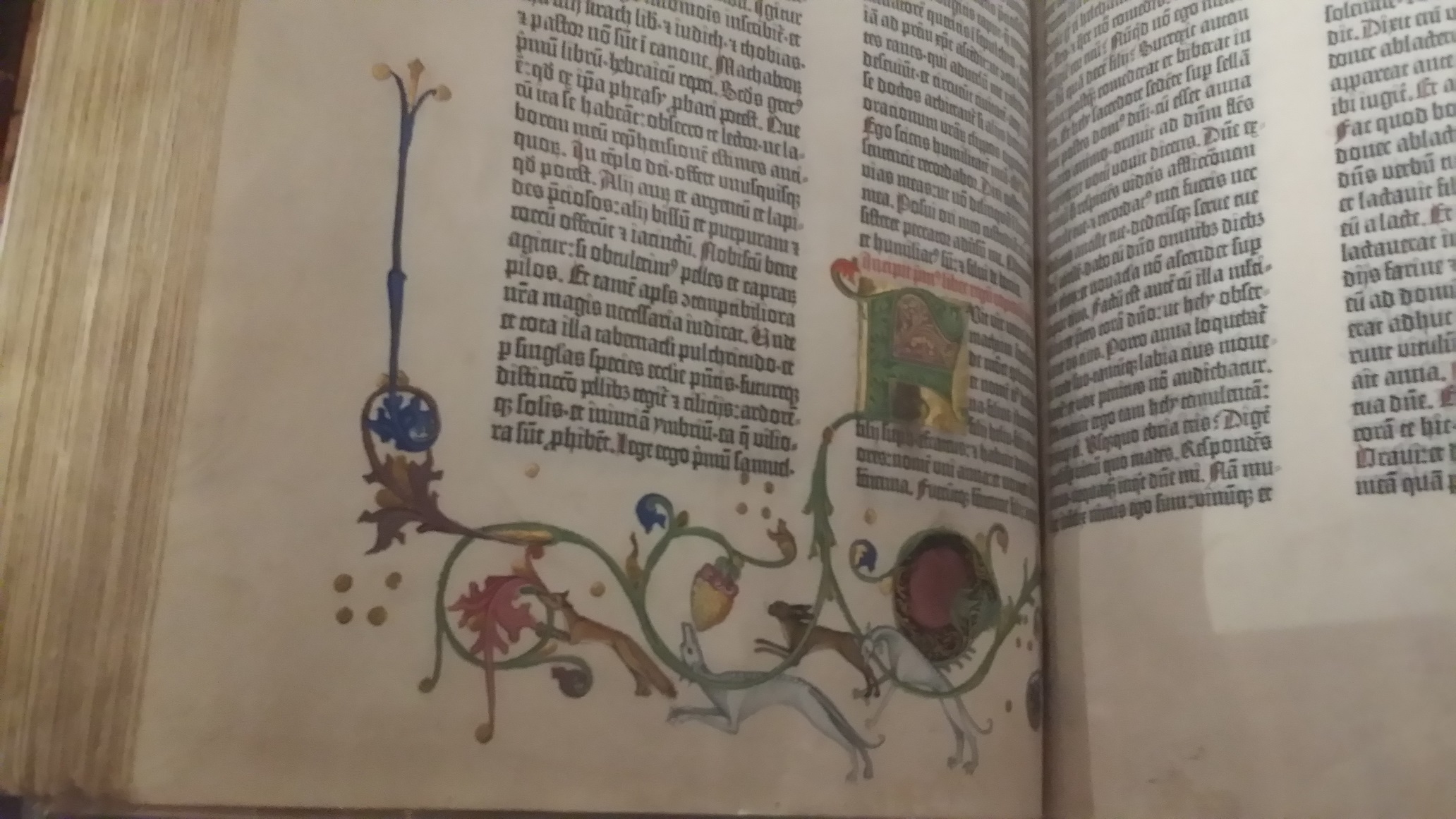

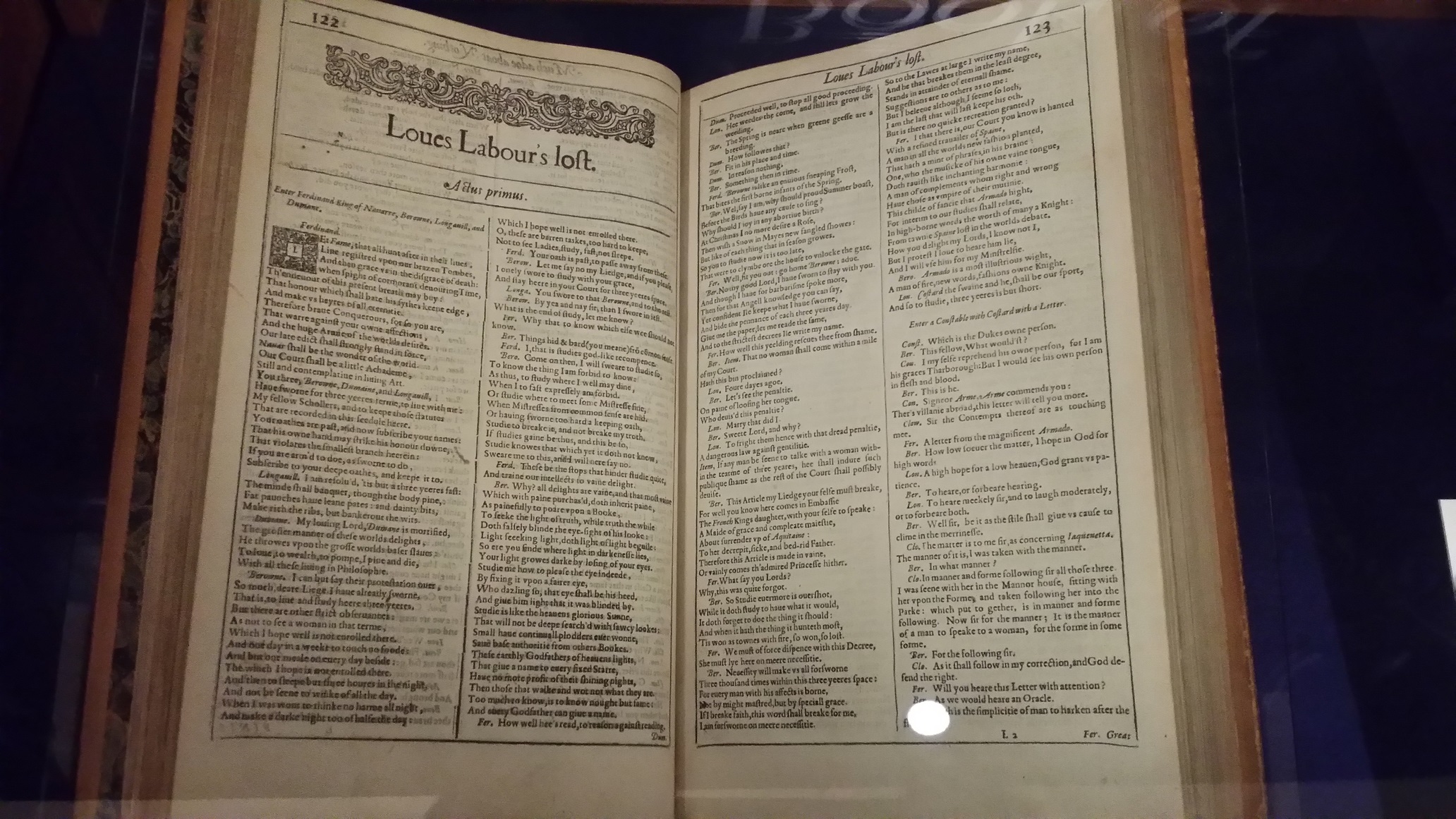

For a St. John's College alum, the Huntingdon Library is a magical place. Their chief highlight is a very fine Gutenberg Bible. A very fine Gutenberg Bible and a Shakespeare First Folio. Their two chief highlights are a very fine Gutenberg Bible and a Shakespeare First Folio. And the Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales. Their three chief....amongst their highlights are a very fine Gutenberg Bible, a Shakespeare First Folio, and the Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales.

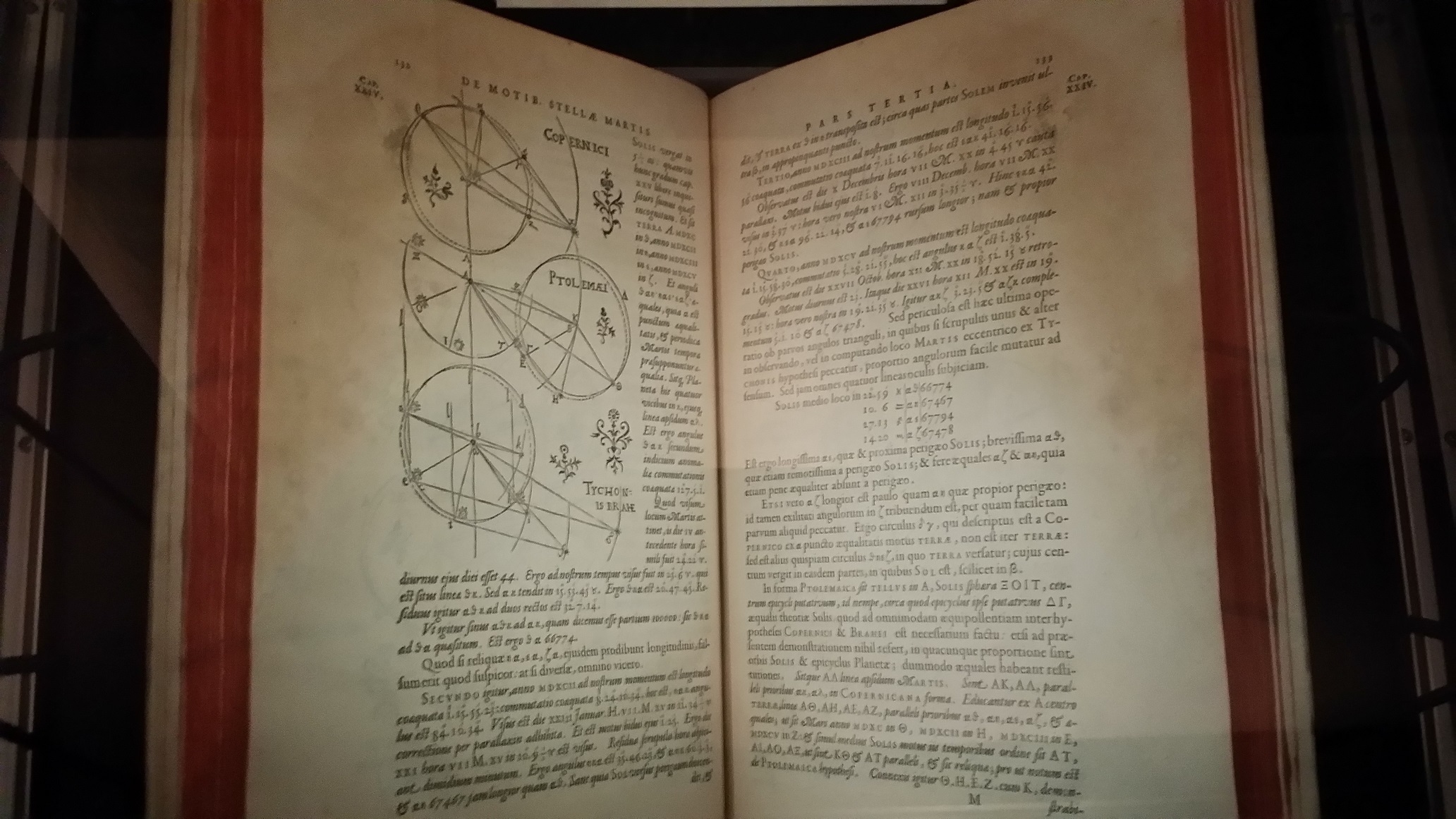

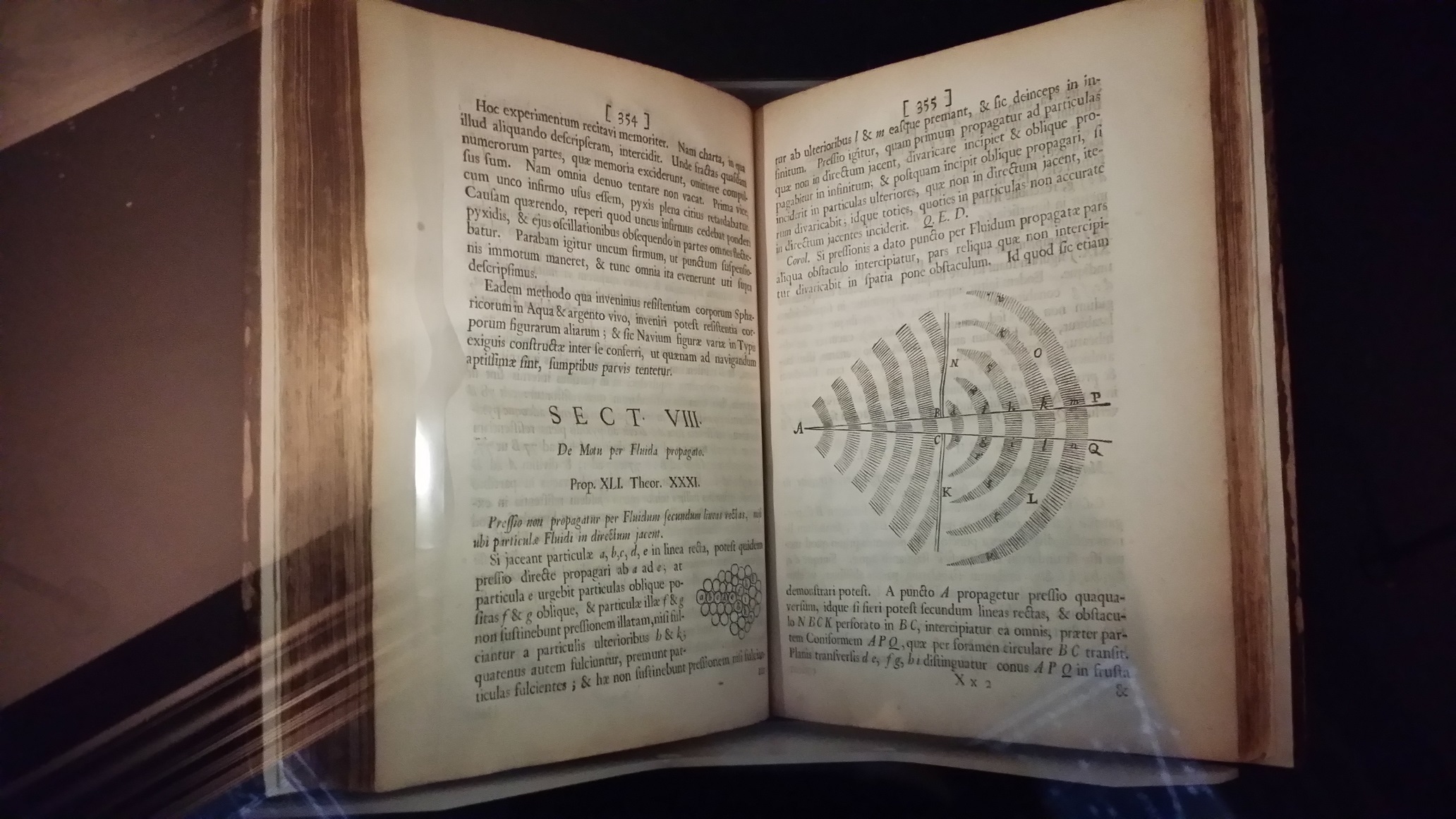

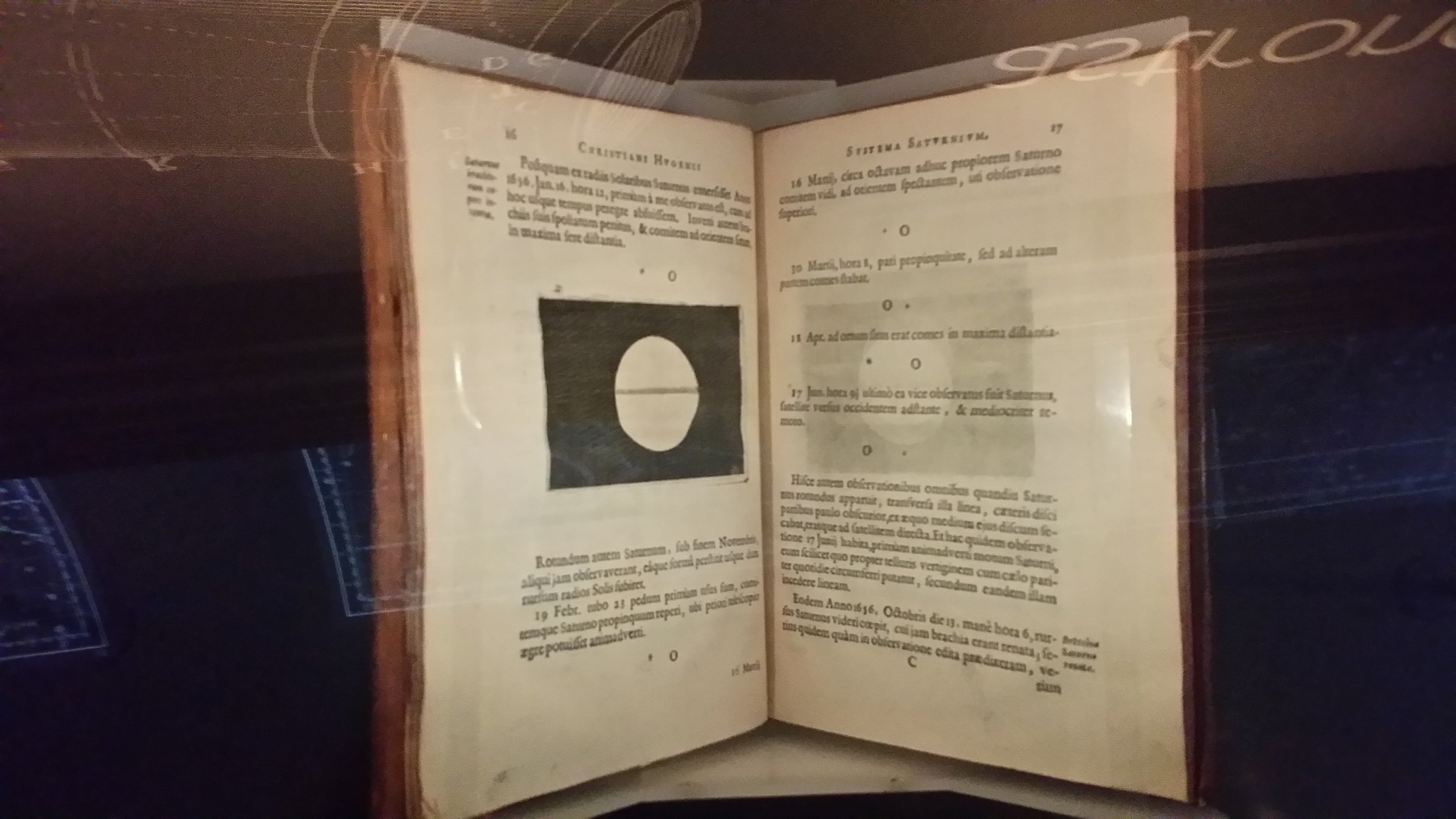

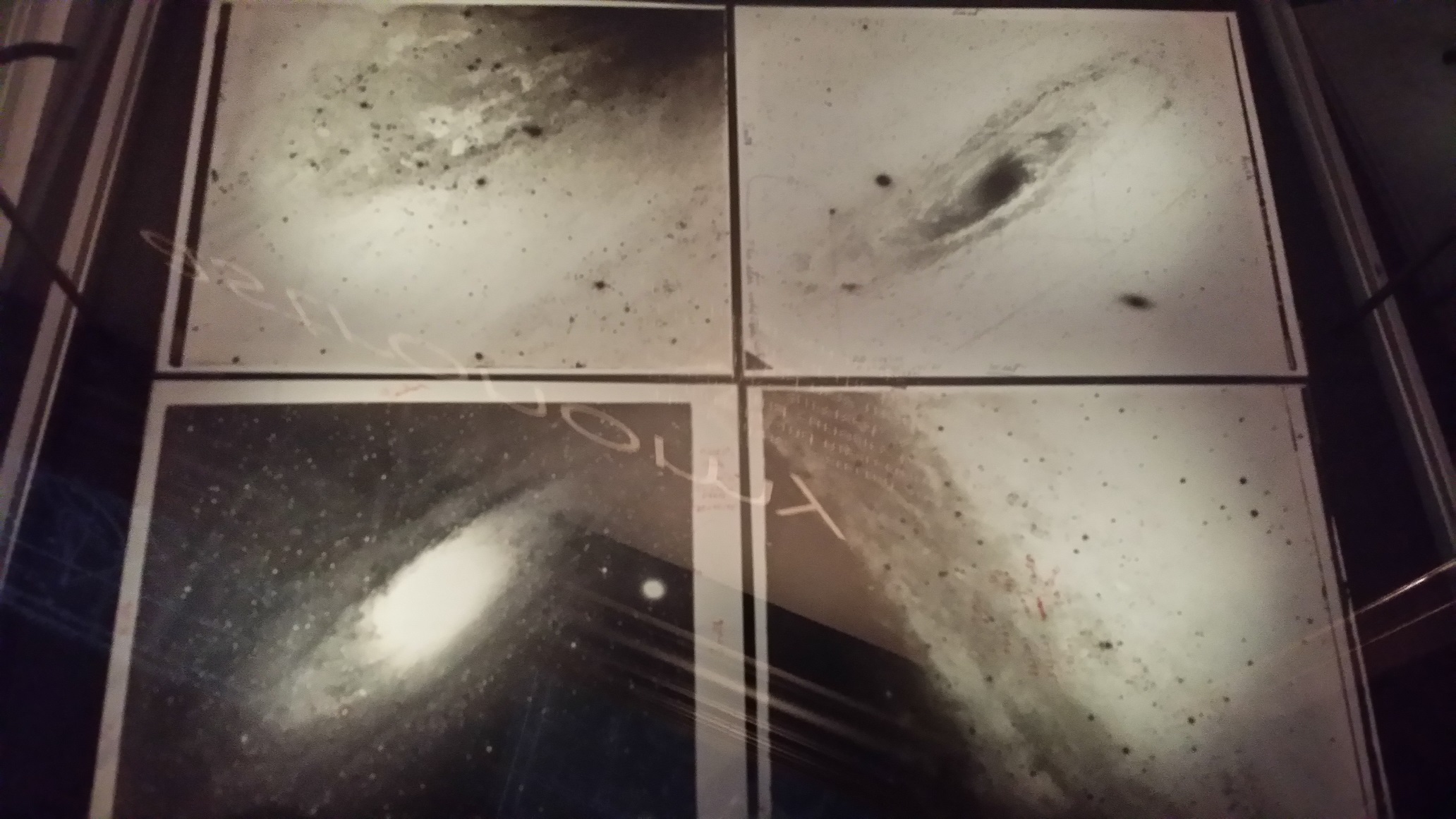

All that was pretty cool in a first room that also had a huge The Birds of America by James Audubon, an early copy of the Declaration of Independence, cool old manuscript maps, and a letter from Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton. But there was more — much more! After an interesting (but not all that photogenic) exhibit on Octavia Butler, I went into Dibner Hall of the History of Science. A history-of-science geek paradise! A second edition of Copernicus; a first edition of Kepler's Astronomia nova — the book where, after years of trying to prove that the planetary orbits weren't ellipses, Kepler finally gave up and announced that the planetary orbits were ellipses; first editions of the books that got Galileo in trouble with the Catholic Church; the first drawings of Saturn's rings by Christiaan Huygens; some of the earliest photographs of other galaxies taken by Edwin Hubble (who had a pretty good telescope). And the pièce de résistance — they didn't just have a first-edition of Newton's Principia Mathematica (the book where he introduced calculus, worked out the theory of Universal Gravitation, and gave us the Laws of Motion that are the basis of Classical Physics), they had Newton's own personal copy! Complete with the handwritten notes Edmond Halley made in it after Newton gave it to him. Inconceivable!

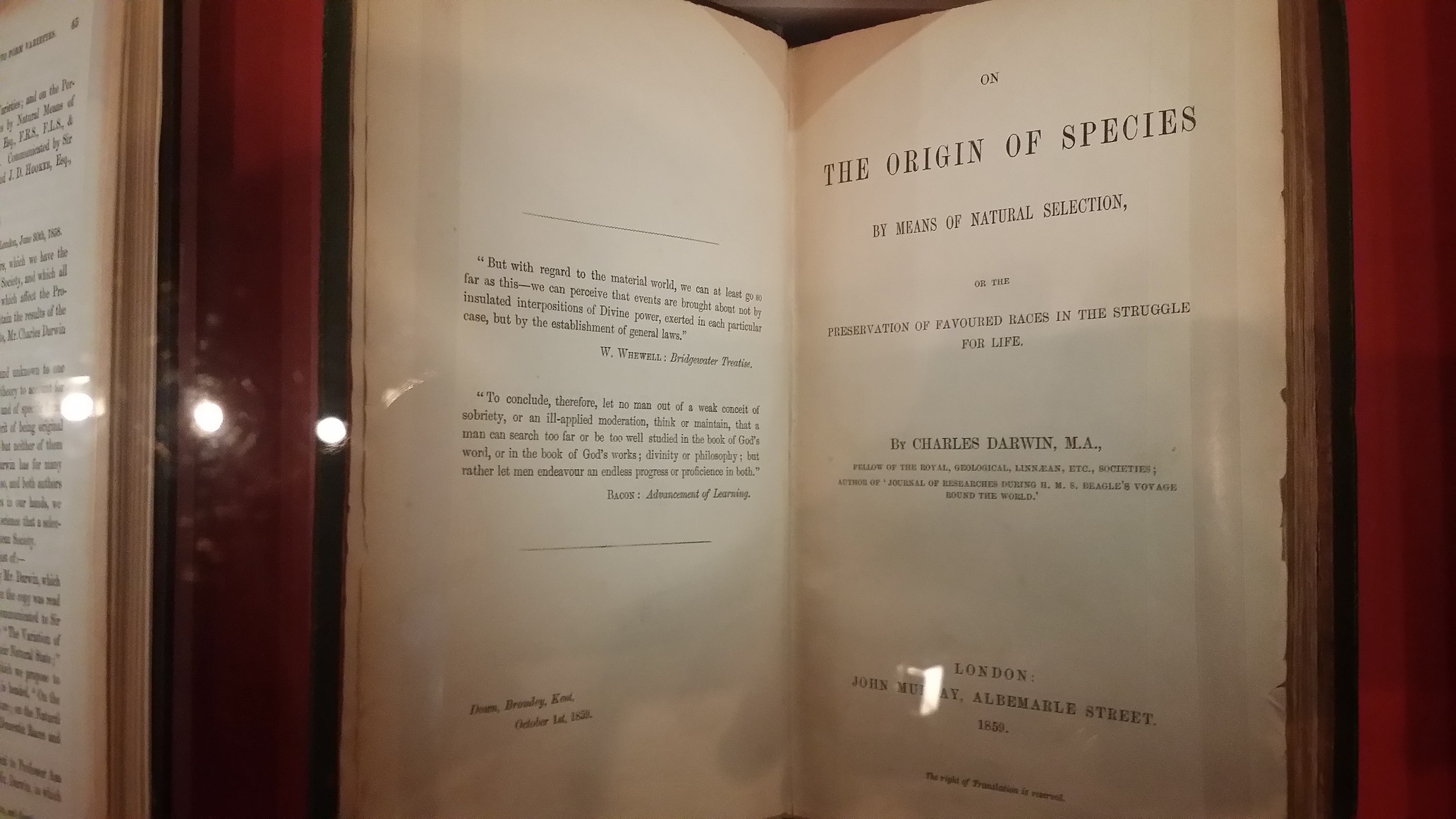

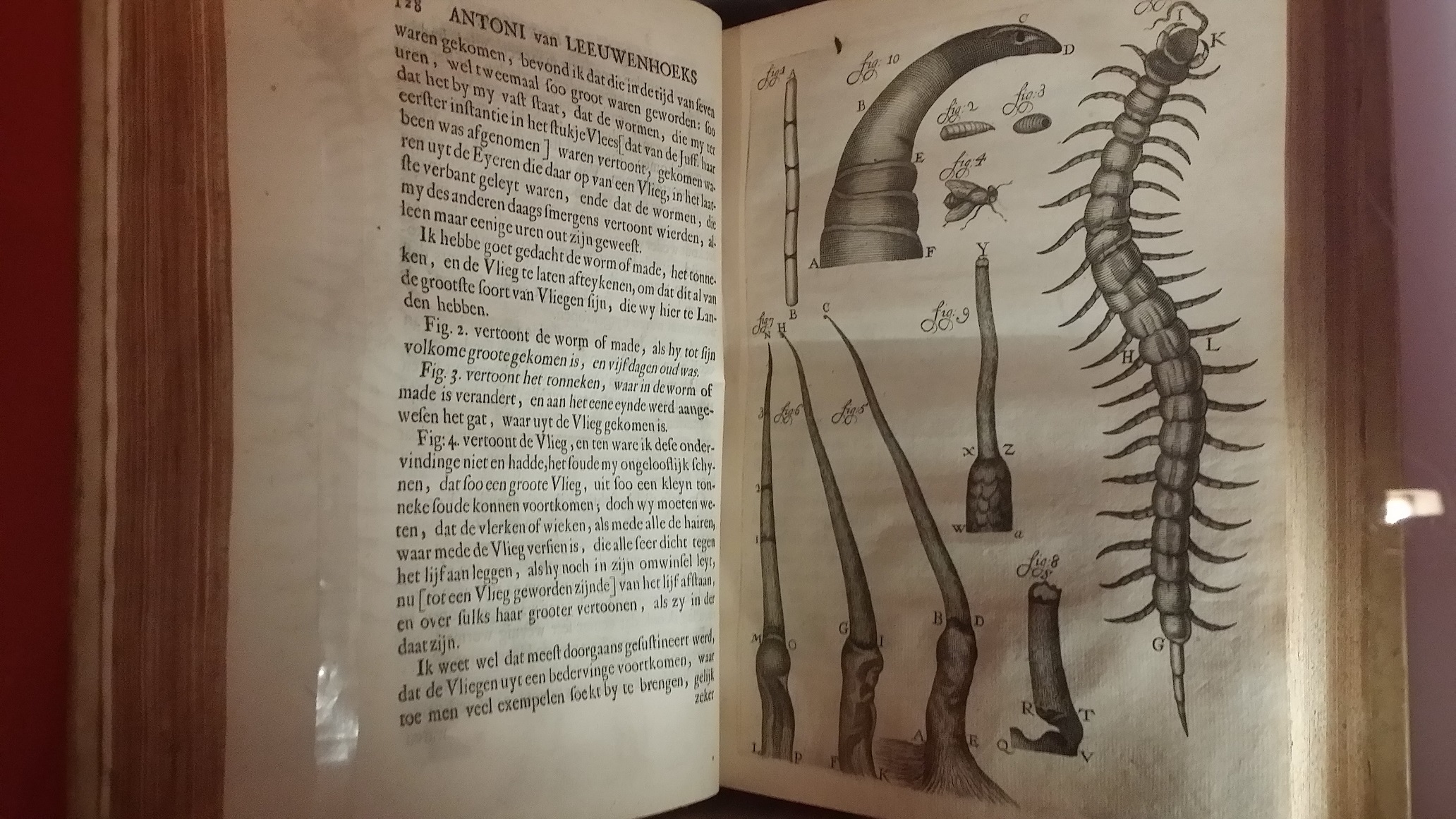

The next room of the exhibit couldn't match that. Oh, except for first editions of The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin accompanied by the Journal of the Proceedings of the Linnean Society in which Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace first published their papers on The Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection. Providing the other half of the story was a first edition of The Proceedings of the Natural History Society of Brünn, wherein Gregor Mendel described the experiments of plant hybridization that showed the laws of genetic inheritance. Add to that first editions of Robert Hooke's Micrographia and Antoni van Leeuwenhoeks' collected works — the foundations of microbiology. Plus Descartes, Lamarck, Cuvier, and William Harvey. The room after contributed first editions of Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell, a second edition of Newton's Opticks, and a first of Benjamin Franklin's Experiments and Observations on Electricity. And these were just the highlights! There was actually much more.

The Huntingdon also has a large art collection. I didn't have much time to see it — and it was mostly 18th and 19th-century portraits anyway (boring!) — but it did have a pretty Madonna and Child by Pintoricchio.

Lunch and dinner with friends were both pretty great, and in between there was a pleasant walk around Old Town Torrance where the jacaranda trees were vividly in bloom.

In the morning Sunday I went to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles. What a great place! One cool thing about it is that most of the fossils you get to see are real fossils, not just casts. Two specialties of the fossil collection are large dinosaurs and ancient North American mammals. A star of the collection is a series of three Tyrannosaurus Rex fossils showing how big they were at two, fourteen, and seventeen years of age. They reached their full size at about twenty years, and are thought to have had about a thirty-year lifespan. Juvenile fossils of T. rex are very rare, but paleontologists think that the young may have had feathers. There was also a spectacular Stegosaurus. A very knowledgeable docent explained to me that the plates along the Stegosaurus' back were ossified, but they were not really bones. They were a modified skin-structure like the scales on alligators and crocodiles, and they were likely used for diplay during mating. Because of their position the plates were of little use in defense, but Stegosaurus had a big spiky tail for that. I also learned that the neck tendons of the big dinosaurs would also ossify, giving the neck enough support to hold up the dinosaur's head -- see the Allosaurus photo below. A couple of Triceratops fossils were also very impressive.

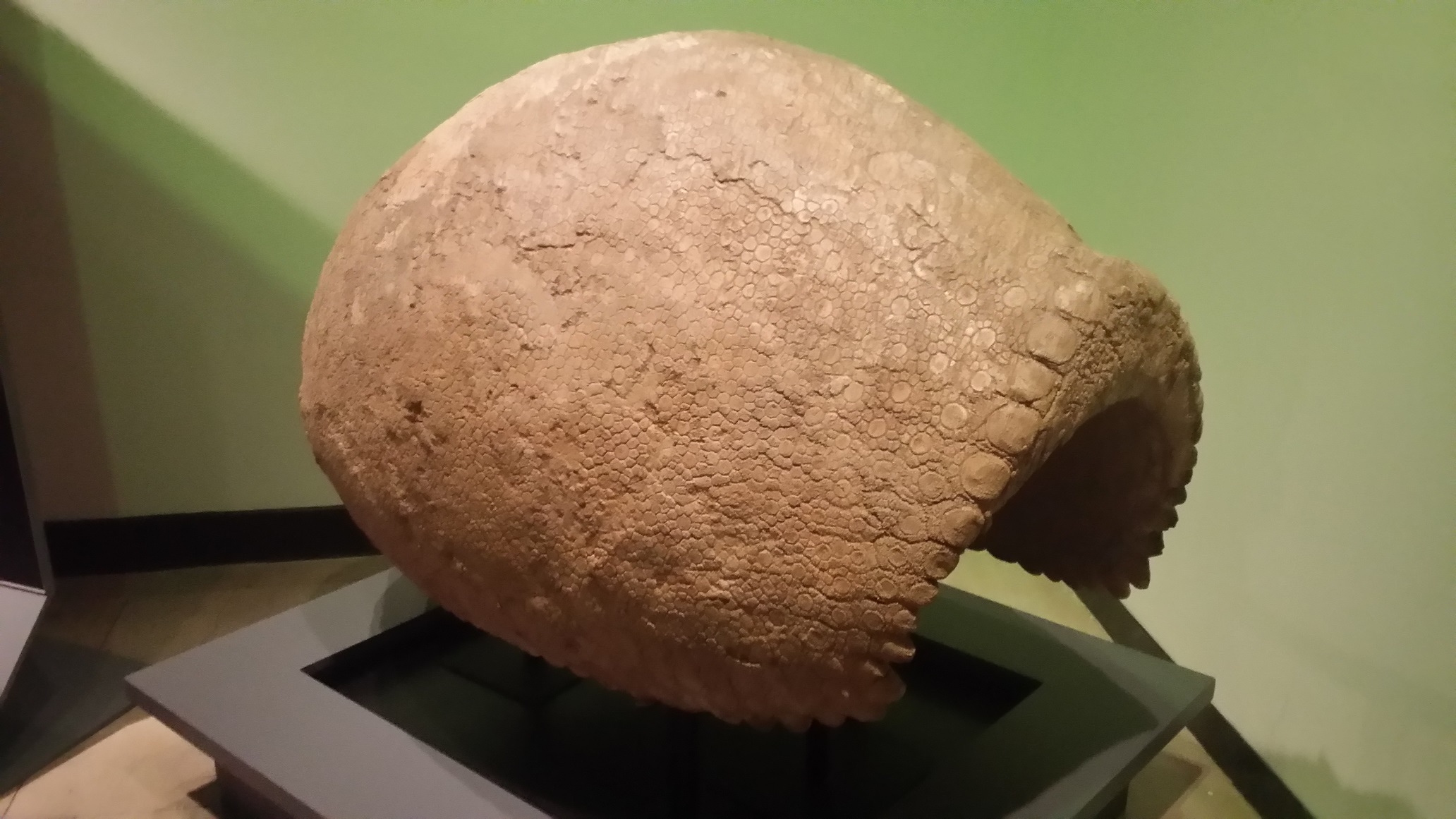

I paid extra for a ticket to the Extreme Mammals exhibit, and I'm glad I did. Among the fossil wonders in the exhibit were a giant ground-sloth, a Tasmanian Devil, a Uintatherium anceps (which looked like a giant, angry hippopotamus), the shell of a huge Glyptodont (an Armadillo of Unusual Size), a narwhal tusk that had to be at least nine feet long, and several sabre-toothed tigers (Smilodon). Given the proximity of the La Brea Tar Pits, Smilodon are another speciality of the museum. Usually predators are just enough bigger than their prey to be able to kill them. If the prey is too small, too much energy is spent catching them to be worthwhile. Smilodon's long fangs allowed it to take on animals much bigger than it was, by leaping onto their backs and using the fangs to sever the jugular vein.

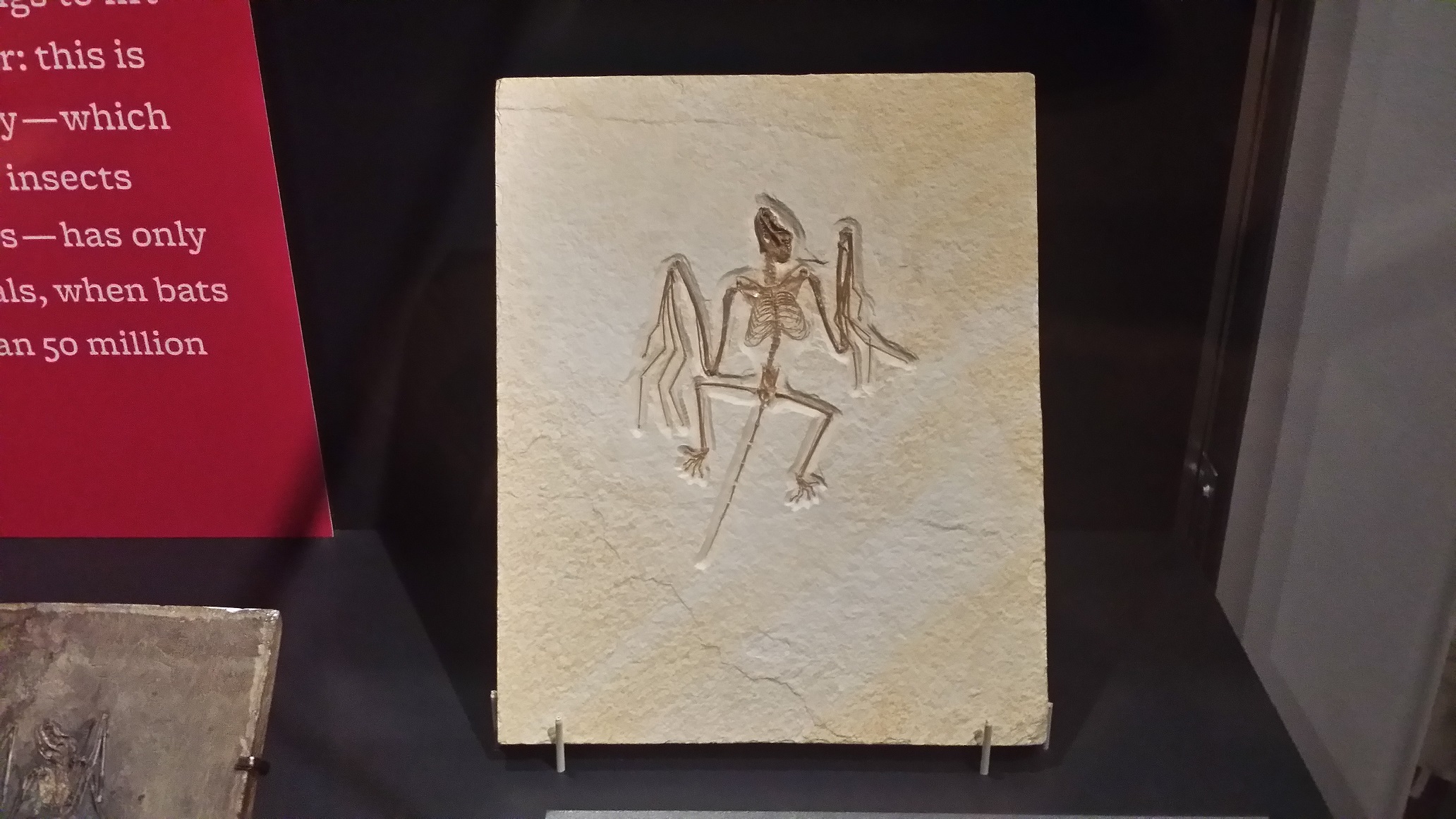

There were some cool bat and proto-bat fossils, including a 52-million-year-old Onychonycteris finneyi fossil that strongly suggests that bats evolved the ability to fly before they developed the ability to echolocate. It has the chest and limbs of a flyer, but does not have any of the skull structures associated with echolocation. It also has normal-size eyes, which suggests that the earliest bats flew in daylight and that the development of echolocation was part of the transition to night flying. Side note: while the poosible lineages are in doubt, the most popular theory is that the mega-bats descended from one of the four families of micro-bats, and that they lost the ability to echolocate as part of a transition back to day flying. The mega-bat genus Rousettus later developed a different type of echolocation based on tongue-clicking, rather than the larynx contractions that micro-bats use.

After the Natural History Museum and a very pleasant brunch with my aunt and uncle, I drove north and east to Big Pine in Owens Valley, where a friend of mine works in the radio-wave observatory. He's working on a cool project. Radio wave detectors can detect fainter signals and be more precise if they are cold, so he's building a housing that will allow the detectors to be cooled to somewhere between 10 and 20 Kelvin! These detectors will be used to study the Epoch of Re-Ionization. The time after the Big Bang is observable due to cosmic background radiation, but from the time the universe was about 380,000 years old until when it was a couple hundred years old were the Dark Ages, when the primordial plasma cooled down enough to form neutral hydrogen atoms, and there was basically no light source to illuminate them. Somewhere around when the universe was 200-300 million years old, condensation of groups of hydrogen atoms generated enough energy to cause the universe to revert to a state of re-ionized plasma, visible to radio-wave detectors that are really, really cold. The detectors will also study the Epoch of Galaxy Formation, which got going somewhere between 400-700 million years after the Big Bang. After a night of camping under the vivid stars in the Yolo Mountains, with hotdogs, marshamallows, and corn roasted over the campfire (and canns of beans heated alongside, I got to tour the observatory. The observatory is run by CalTech, so it wasn't an actual NASA control room, but I did get to be in the control room of a huge radio-wave collecting dish.

As fun as the weekend was, I needed to be at work the next day, so I drove north along the Sierra Mountains. I wasn't in any hurry, so if I saw an interesting dirt road I drove down it. The desert scenery was tremendous. The panaorama at the top of the page is from Sage Hen Summit (8,139 feet) in Mono County, CA. In the afternoon I stopped at Mono Lake, near the east entrance to Yosemite. It's about 2.5 times as salty as the ocean (but it tated much like ocen water to me), and it is home to billions of brine shrimp, which make a tasty feast for hordes of migrating birds. Sulfur-containing spring water bubbles up through the lake, and the precipitating sulfur forms eerily cool rock formations. I walked around in them at South Tufa, part of the Mono Lake Tufa State Natural Reserve. The only reason you can is that water diversion for Southern California led to a great lowering of the lake-level. Because of its ecological importance the diversions have been reduced and the lake is being restored to an earlier, higher level. I feel fortunate that I was able to see the rock formations up close. I plan to go back in October, when about a million and a half grebes will be staying there as part of their migration--apparently they are so thick it looks like you could walk across the lake on their backs. One other migrator of note is the Wilson's Phalarope. These fist-size birds stop at Mono Lake in mid-summer after breeding in the northern U.S. and southern Canada. After molting their feathers and doubling their weight eating brine shrimp they head to South America, travelling about 3,000 miles in an astonishing 3 days!

After more dirt-roading, I wound up at Lake Tahoe for a beautiful sunset. The whole trip was 1,400 miles in three days, but I felt like I had seen enough cool stuff to last a year. It took me about three days to recover, but what an amazing weekend!