Lonely

A True and Fictional

Tragical Historical yet Comical Account

Of the Myriad Mysteries and Enigmas

Of

by

Clayton Bess

Chapter One only

All Rights Reserved: This manuscript or any portion thereof may

not be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author or

his agent.

© Robert Locke 2006

http://webpages.csus.edu/~boblocke/index.htm

Lonely Island

Chapter One

The Mysteries

They

say we ate people. I think probably we

did.

But

that was a long time ago. I was not even

alive. I myself did not eat the people,

not myself. Our people did. If they did. And although

I think they did, what does that have to do with me? What does that have to do with today? Perhaps we will need to eat people

again. Things happen that way sometimes

when you live on an island.

They

say we are a friendly people. I do not

think I am friendly, so much. I do not

think I am unfriendly, either, so

much. I am who I want to be: Toromiru.

From

the way I am writing this, you are going to think I am mad. And perhaps I am mad. Perhaps that is the

reason I am writing this, because I am mad.

I am mad because people from so many different places around the planet keep

coming here to look at us. They want to

take our photos. My brother is very

handsome and my sister is very beautiful; so these many people from their many

places want photos of my brother and sister especially. My brother says, “Why? Where will I see that photo?”

The reason my brother says that? Perhaps my brother is mad, too. He knows that when the people go back to

their homes around the planet, then perhaps they will use that photo in a story

that perhaps they will write about us. So

many different people are always writing about us in so many different

languages. They all descend upon us

wanting to know about our island because our island is “mysterious” and our

island is an “enigma” and so what? And we

are the people who live on this “mysterious and enigmatic island” and so

what? And so they put our photos in

their stories. And sometimes what they

write is not true or even close to true, but they have our photos anyway. But when my brother asks them why they want

his photo, he says it with a grin, and they go ahead and take his photo

anyway. But I think inside, perhaps, my

brother is not grinning.

My

brother is the one who takes the different peoples who speak English. I call them the Englishers: the Americans and English and Australians, of

course, but also usually the Germans and the Japanese, and all of those who

understand the language of English better than they understand the language of Spanish. My sister is the one who takes the Spanishers. Those are the different peoples from

I usually follow my brother

so that I can learn the English better.

I am not allowed to lead the tours yet—if ever?—because I am too

young. Or that is what they say. But that is not true either. I am certainly old enough, but perhaps no one

trusts me enough, which is why I ask—"if ever?"—in

the way that I do. There is

always the matter of the lying and the doubting vis a

vis the telling of the truth, that which is prickly.

I can take the Spanishers

better than my sister because I have read many more books than she. And because I have followed my brother so

many times I can do the Englishers equally good as to him. Perhaps better because I am always listening

to the Englishers talking to each other at the same time my brother is talking

to them. So I know the questions they

have but do not have the opportunity to ask him. Or perhaps they do not want to ask him for

fear of offense, and often these questions are indeed offensive, but then, what

is to be done about that?

My brother sometimes reads

some books, but so do I. And I

listen. And I always tell the truth,

except out of playfulness. My brother

sometimes makes up the truth. If he does

not know an answer to one of their questions, he might open his eyes wide and

lower his voice to a whisper and say, “It is a mystery.” He knows this always works because everyone

who comes here knows already that our island is full of mysteries and enigmas;

in fact, as I have indeed explained already, that is exactly why they do come

here. And what they do then, when my

brother tells them it is a mystery, and opens his eyes wide? Then will they nod their heads very slowly

and open their eyes wide also, like my brother, and raise their eyebrows. It is very comical. You would laugh to see it.

My

sister makes up her own truth all the time because she does not really know

anything, and that is the easiest. The

other day at Rano Raraku a man from

My sister then replied,

“Yes, between two and three thousand years!

No one knows! It is a mystery!” My sister learned that trick from my brother,

you see. Only since she was speaking in

Spanish to the Spanishers, what she actually said was, “ˇEs un misterio!” In Spanish, you are called upon to put the

exclamation marks at both ends of the sentence, which of course doubles your

exclamatory effect. And because of the extra

vowel sounds in Spanish, I have found that you can open your eyes even wider

and you can stretch out “misteeeeeeeerio” for a longer time. In English, you would have to say “mysssssssstery”

to say it long enough to open your eyes wide enough to get the same effect, and

that would make you too silly to take serioussssssssly.

The Frenchman then turned to

his wife and translated into French for her:

"Ah, oui! Un

mystččččččččre," opening his eyes wider, I believe than anybody I have yet

seen. The French are even more

impressionable than anyone else, as you will see later.

I have

read very many books about our island and our people, but still my brother and

sister do not let me lead the tours yet.

I think they think I know too much.

I think they think I will get confused.

Perhaps they are right. The more

you know, the more you know you do not know.

One

of the good things about following my brother or my sister when they take the tours

is that the people begin to look upon me as one of the mysteries. I never say anything, and that is mysterious

to most people. And when there are

people who are my age, they are drawn to me because of my mysteriousness. Also because I am their

age. Have you noticed that? Young people like to be with young people,

especially if they are traveling with their parents who are, often, very dull to

them. And so I wait. I look at the young people with my eyes, and

I know they will come to me. At night, I

make sure that I am near their hotel, and that they see me. Then they will always come to me. They always want to sneak out of their hotels

at night to the same places they went during the day, with me, alone, in the

darkness, with only the moon to show us the island.

I

can drive. I am not allowed to drive,

but I drive anyway. My favorite times

are when the young people want to go back out to Rano Raraku, which is my

favorite place. This is the quarry where

the moai were carved out of the volcano and where they still stand, still

waiting—after all these centuries—for their carving to be finished so that they

can be moved to the shore. The mana of

the moai is like electromagneticity, I believe, as I think I understand that

word; the air hums with their mana; the breezes move among the moai and through

the waving grasses like fishes in schools, and you can gulp them; in the

moonlight in the dark you can breathe the mana into your own body, and you can

be one with them.

Figure 1: Here are a few of the moai at Rana

Raraku. Can you feel the mana of the

moai from this photograph? I think

not. I do believe you must be with the

moai to feel their mana. And the mana of

the moai is most powerful at night, when a camera does not work properly. A photo from a camera is not the best way to

capture moai, to capture them as you might a school of fish, in one gulp.

The

moai at Rano Raraku face down the hill, those that are not fallen down. All of them stand at different heights, all

of them from one-quarter to three-quarters buried, some with only the tops of

their heads showing, looking as though they are trying to keep their noses

above the soil which each year grows a little higher up their necks. Most of the moai are straight up and down

upright, but some of them are at an angle, as though they are drunk. In the moonlight, they are beautiful, and

they are sad. And if it is a girl that I

take there in the moonlight to Rano Raraku, she might cry. If it is a boy, he might be completely quiet

as we walk among my ancestors on the edge of the volcano. There is no talk of the mysteries because the

mysteries are right there revealed to us, surrounding us, blowing the breezes

that wave the grasses at our feet.

Figure 2: Here is another angle at the moai, again

hoping to capture the mana of the moai for your eyes, again probably failing by

nature of a mere photograph.

If

I can get my compadres to dare to climb to the top of the volcano, one of the

highest places on the island, we can see the ocean all around us, shining a rippling silver in the moonlight. For me this is something truly special and

stirring to my soul. For the others,

they are then thrilled. Or they may be

terrified.

One

girl named

She

kept saying how far we were from anywhere.

Even though she had flown over the broad Pacific Ocean from Kansas to the

island of Tahiti, and

from Tahiti the two thousand four hundred miles across that same ocean to our

island, and even though she had been on top of Rano Raraku in the daylight, it

had not yet sunk into her head how far she was from the rest of the world. She kept saying, “What if…” but she could not

finish the thought. This is what I think

she thought: I think she thought, “What

if this island sinks into the ocean?” or

“What if the plane tomorrow cannot take off before it reaches the edge of the

island, and we crash into the ocean?” which always appears to me a distinct

possibility, as I watch the airplanes come and go in their little

hugeness. Or perhaps

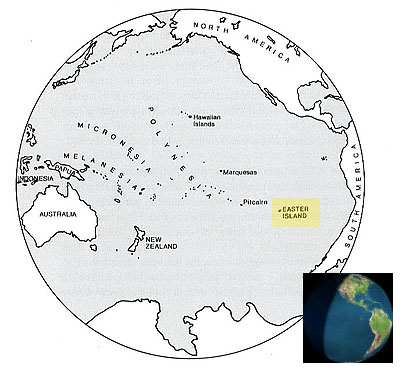

Figure 3: Where

These

thoughts of

There was one of the Englishers who was named Daniel. He

looked older than me by perhaps a year or two, with the soft beginning hairs of

a beginning beard. Perhaps he was seventeen

or eighteen, although I have found it very difficult—with so many peoples of so

many places—to guess at age because their styles of dressing and of acting are

so different. I think, too, that Daniel

was from one of the islands of

I think Daniel had read in some of

the books about how our people are sexy, and I think that is what Daniel

wanted: sex. But the ways of Daniel were gross, and I

think none of our people would want to play with him. Our people may be sexy and very playful, but

they are not gross.

Daniel wanted me to show him The Cave

Where Men Are Eaten. On some of our maps,

it is called

I think Daniel was attracted by the

name of the cave. He wanted me to tell

him about the great battle of “The Long-Ears” and “The Short-Ears” and when I

would not—because that is a story I do not like, although I will tell it to you

later—Daniel then wanted me to tell him a different bloody story. This other bloody story that he must have also

read about somewhere in the many books written about our island was about a

different battle. In this other battle a

warrior said to his men, "Bring me the body of the man with the beautiful

name so that I may eat him." Daniel

wanted to know what that name was. I

pretended I did not know that story because that is also a story I do not

like. I did, however, know the

name. And I shall tell it to you (in a

whisper) at the appropriate time.

But

for now, I just want you to know that after I showed Daniel The Cave Where Men

Are Eaten, I left him there alone, because of repugnance and because I was

afraid he would take the flashlight from me because he was much more powerful

than I. I climbed out of the cave, and I

did not come back for him. That was

probably dangerous for him, on the rocks above the ocean, but there was a full

moon, and his ways were gross. I think

he may have tried to make trouble for me after that, and I think that is one of

the reasons why my brother and sister do not let me lead the tours, even though

I am qualified. Perhaps they are

right. Perhaps they are not.