Living, Dying, and Mr. In-Between:

A Biographical Fragment

Of Robert and Richard Locke

By Robert Locke/Clayton Bess

July 1, 2004

The phone rang at 2:13 in the morning; I know because I looked at the clock. I wasn’t surprised, not really at all. I was alarmed, of course. The phone ringing by the bed in the middle of the night is a terrible noise. This was happening often and, as always, I answered prepared for the worst. And this time it was the worst: my mother’s exhausted, scared voice, “Richard needs you to drive him to the Emergency Room.”

I had gone whitewater rafting that day with Bill and Vivian, Tom and Mary and other friends, and we had come home and drunk a lot of margaritas and gone to bed late; so I wasn’t thinking or seeing well. Could I drive, I asked myself? Was I safe? I thought yes, but who can be sure, awakened from a dead sleep at 2:13 a.m.?

The irony had not been lost on me, when I had declared exuberantly to everyone in the raft that perfect day on the whitewater, “I must do this! I must come out and do this kind of thing to remember why I am alive!” The irony had not been lost on me when I got home and called my parents’ house and Richard’s first words to me were, “Did you have fun?” before he had to excuse himself to rush to the bathroom to vomit. The irony had not been lost on me that while I was out fighting whitewater to find joy in life that my brother was fighting for life itself.

Bio:life—graphy:writing. Death:the end of all writing. My brother Richard and I have been kindred yet combative spirits all our lives. My bio is his, his is mine, and yet each of us has so much more and we are so different, and so alike.

That 2:13 a.m. phone call would have been inevitable whenever it might have come, but the fact that it came after such a perfect day in my life—September 13, 1996, the day after my mother’s 83rd birthday, with good friends around me, nature, beauty, adventure—throws that day into horrific relief in my memory. No, it wouldn’t have made any difference if I had been at my parents’ home that day because Richard still would have been retching all day long without my being able to help him, but did I have to be having so much fun? Richard had just undergone his third chemotherapy for a fast-growing lymphoma, and each chemotherapy had racked his body worse than the one previous. He had his drugs to relieve his pain and his various symptoms of nausea and diarrhea and convulsions, and he took the drugs on his own when he felt he needed them most. His morphine, however, disturbed me very much that night.

“I couldn’t keep the morphine down,” he told me after I had helped him into the car and started for the hospital, “so I shot it intramuscularly.”

So many alarms rang through my deadened brain. Oral morphine? He shot it? Intramuscularly, is that different from intravenously? And now he’s having trouble breathing? Could the morphine be the reason? Could it be an air bubble from the hypodermic? I don’t know anything about shooting drugs, though Richard was expert, shooting speed, too often, too long. I knew Richard was annoyed by all these questions I was asking him; he just wanted to get to the ER, but from the looks of him, I was afraid he might be passed out before I even got him to the ER and I might have to give the doctors all this information on my own.

The looks of him...

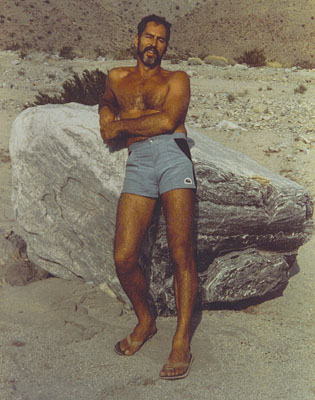

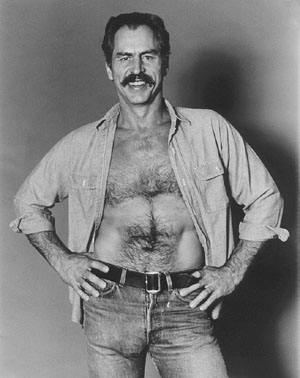

This was Richard Locke. Probably everyone in the gay communities of San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles and Toronto knows Richard Locke. The porn star. “An icon!” so many have written to me and my parents. An icon of male sexuality, an “aw shucks kind of guy”, handsome, extremely well-built, with intelligent eyes and a rugged persona.

The looks of Richard Locke...

A couple of weeks earlier when I had taken him to the hospital—he was bald from the chemotherapy, walking stiffly with a cane, his lips pulled down in a grimace of pain—the nurse had asked me, “Are you his son?” Richard heard that, and I know that that irony was not lost upon him.

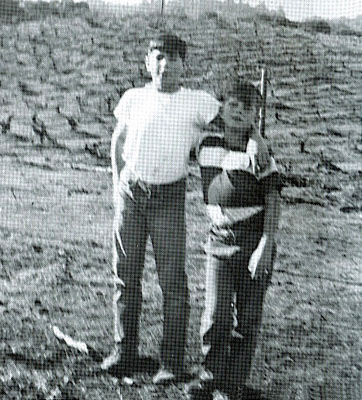

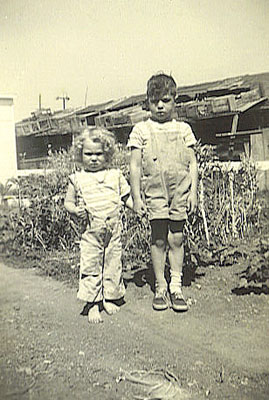

Richard was born three and a half years before me. He was the third child. I was the fourth and last. My father has often joked that I was neither expected nor wanted but he claimed I was a true joy, nevertheless. “Earned your keep right from the beginning,” he told me innumerable times, referring to the fact that I was born on December 30 and so they were able to deduct me from their taxes for the entire year of 1944, that hard year at the end of World War II when everything was still rationed. (My mother still has some ration books in my name.)

I had watched with private horror how ugly Richard had become during those last months. Richard knew, too. He told me that a child had been scared of him in the store. “That face in the mirror!” he said to me. I had already remarked to myself—with anger at myself at the thought—that he looked just like Nosferatu.

Yet I had reminded him just the week before, when I was driving him on an errand, “Richard, you’re humming. Remember this. You’re going to get your chemo tomorrow and you’re going to feel rotten for another week or more, but you’re humming now, and you’ll be humming again in just a little over a week.” And when all six chemos were done, the Lymphoma would be gone, his hair would grow back, and he would be well and looking again like Richard Locke. Except without all the muscles. “It’s just time, Richard,” I said. “Just a matter of getting through it.”

I’ve discovered about myself through the years that I keep trying to find the positive. I also keep trying to remind family and friends of the positive whenever they are struggling through hard times. I think that’s probably because I am at heart so dark and negative. But to be honest, what is the use of laying negativity on your family and friends? My mother told me recently a story about me that I had never heard before, a story that pleases and surprises me about my nature. When I was in kindergarten she was called to school by my teacher and my mother thought, “Oh, what’s he done?” The teacher told her that she was worried about me because whenever all the other kids were off roughhousing, I would just sit in my seat and hum. My mother said, “Well, at home he just sits in the window looking out and singing to himself.” I guess they just shook their heads at each other, but I wonder that they both found this worrisome. I kind of like that little kid.

When I got to the hospital I parked illegally at the curb and rushed to get a wheelchair for Richard and got as quickly as possible through the first hurdles. He was still alert enough to give the admissions nurse the names of some of his medications. I knew them pretty well too, because I had become very involved with his sickness and his doctors in the past year, and so I was able to supply the names he couldn’t remember. Then we were inside the ward, and we had to go through the list of meds again. I tried to emphasize to this new nurse—or doctor or whoever that blasť fellow in the ER was—that Richard had shot some morphine intramuscularly. The man looked bemused but unconcerned. Richard was gasping. They had given him an oxygen tube under his nose immediately, but now he asked for a mask. While they were putting the mask on him, I went back out to the car to park it legally and fetch his hospital bag with his medications; we had learned to have a hospital bag made up and ready. I also got his pillow.

That pillow was important to him. The first time I had taken him to the ER we hadn’t thought of the pillow, and Richard had to spend his first night with those dinky pillows the hospital provides. Richard’s own pillow was two thick down pillows stuffed into one case, heavy and solid yet soft, like Richard himself. After that first time, I always made sure to bring his pillow when I took him to the hospital, even this time.

When I came back into the ward they had the mask on Richard, and I stood by his side as he sat up on the gurney, trying to keep himself upright, but leaning, off-balance. At one point, his eyes rolled back into a fixed stare at the ceiling. I had seen him do something like this a few times in the last several months, making an expression of pain and boredom which I had always secretly laid to his overacting the invalid. Richard loved for people to know his pain, all his life.

Richard was public with everything, with his thoughts, with his body, with his pain. I think I am much more private, although people who don’t know me well would laugh out loud at that notion. I come across, I know, as a pretty flamboyant, outgoing type, plain-spoken, fun-loving, loud, maybe even garrulous, and most certainly a teller of longwinded stories which I hope, nevertheless, people find pithy and humorous. Perhaps all of these attributions are true, and perhaps they are not inconsistent with what I consider to be a somewhat shy personality. But pain I try to hide. Not Richard. Pain, annoyance, anger, bitterness, frustration with huge and tiny things—he always dwelt on them openly and at length to anyone who would listen, and I think it was actually with some sort of pleasure.

Living in my parents’ house, Richard kept them awake through long nights with his loud retchings and hackings. It must have been awful for all three of them. I believe I somehow, somewhere, held it against him, though I hate that thought now. “That’s Richard,” I would tell myself and try my best to make it right, make him more comfortable, ease my parents’ fears, talk them all through it, looking forward to the cure months down the line.

Seeing his eyes fixed on the ceiling at that moment in the ER, my first thought again was that he was overdoing it. Then I saw that his pupils were so dilated that I could see only a tiny ring of the hazel of his iris. “Richard,” I said to him. “Richard? Richard?” The blasť fellow heard me, broke from the group he was talking to, looked sharply at Richard and shouted full-voice straight into his face, “Richard!” Richard’s body jumped and his soul came back into his eyes. He had been gone. For that one moment, my brother had been gone to some dead place. And I had thought he was merely overdoing it.

That’s when I started trembling, when I knew that I was way over my head in deep water running fast, and I had to start swimming as hard as I could go. My brother needed me, yet what on earth could I do to help him?

This is approximately one-eighth of the story. NOTE: Sept. 19, 2015. I used to have a note at this point inviting readers to contact me by email if they wanted to read the rest of the story. I did this originally so that I could have control over who got to read the rest of the story because it is so personal; I didn't want my sister, now deceased, to stumble across it. Wow, through the years since July 1, 2004 when I put up the story, I was amazed at how many did contact me for the rest of the story. And I did send the file to all of them. I have posted a few of their very dear, meaningful responses along with personal photos from Richard's own photo album in the link below "For anecdotes about Richard".

But now, having turned 70 with a very ill three weeks of terrible head pains last December, plus what I think was probably a first heart attack a week ago, I realize I may not be around much longer to contact by email. So I think I had better put a link here right now to a pdf containing the rest of the story. I warn you. It is grim.

The link below is to the complete story minus the photographs, so to get to where you left off above, do a FIND command for the word: "trembling". That will take you to the final paragraph above.

For the rest of the story, click here.

For anecdotes about Richard, click here.

Copyright © 2004, rev. 2015 Robert Locke

All Rights Reserved